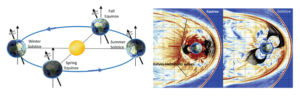

As Earth spins around the Sun, our planet’s slight tilt creates seasons. Now, research from two NASA space missions has found how the same tilt also influences seasonal differences in space weather – conditions in space produced by the Sun’s activity.

Space weather events produce the beautiful glow of the northern and southern lights, but, if intense enough, they can also endanger spacecraft and astronauts, disrupt radio communications, and even cause large electrical blackouts. Since space weather is created by particles and energy sent from the Sun, it varies with the Sun’s 11-year cycle of activity – the solar cycle. But space weather also varies on shorter timescales, such as seasonally and daily.

The new results, published in the journal Nature Communications, found that the seasonal differences are caused by a phenomenon known as the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability. This instability forms curling waves at the boundary between two regions – such as different layers of the atmosphere or between air and water – flowing at different speeds. These waves sometimes occur in Earth’s atmosphere, resulting in unique cloud formations that look like a series of crashing ocean waves. In space, these waves are composed of charged particles that are energized and pushed toward Earth, resulting in enhanced space weather effects.

The new findings confirm that Kelvin-Helmholtz waves are more commonly produced during the spring and fall equinoxes. During the equinoxes, Earth is not tilted toward or away from the Sun. As a result, the orientation of the Sun’s and Earth’s magnetic fields is ideal for forming Kelvin-Helmholtz waves. When Earth’s magnetic field is tilted at extremes toward or away from the Sun – such as during the summer and winter solstices – few Kelvin-Helmholtz waves are created.

“We have discovered that Kelvin-Helmholtz waves in the space around Earth are seasonal, which explains an important factor in the seasonal variation of space weather,” said the lead author on the new study, Shiva Kavosi, a researcher at Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida. “These waves are ubiquitous and can be found roughly 20 percent of the time around Earth, but after monitoring over an entire solar cycle, we now know there are more chances observing them during certain times of the year.”

To make the discovery, scientists used 11 years of data from NASA’s Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms, or THEMIS, mission, as well as four years of data from the Magnetospheric Multiscale, or MMS, mission. “The unique orbits and long period of observations by THEMIS made this discovery – which was first theorized in the 1970s – possible,” Kavosi said.

By better understanding how Kelvin-Helmholtz waves form due to Earth’s seasonal tilt, researchers can better forecast its effects and plan accordingly to ensure spacecraft and astronaut safety. “Additionally, space weather forecasters can now add this component to their models for better forecasting,” Kavosi said.